Traditionally, discourses on colonialism tend to focus on the expansionist policies of European powers and the dependent colonial franchises under their control, but as Patrick Wolfe writes in Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology (1999), “what if the natives themselves have been reduced to a small minority whose survival can hardly be seen to furnish the colonizing society?” (Wolfe 2). Settler colonialism understands the dispossession of indigenous persons to outweigh the colonial interest for their labor; as Wolfe indicates, “Native (North) Americans were cleared from their land rather than exploited for their labour” (Wolfe 2).

While a minimal understanding of the Western Reserve can only be formed in the context of both settlers and indigenous peoples, it is important to inspect the mechanisms by which settler colonialism was practiced in the region. On May 11, 1792, the Connecticut General Assembly designated 500,000 acres in the Western portion of the reserve for settlement by those Connecticut residents who had accrued over $800,000 in debt or more, earning the region the nickname of “Firelands” (Lupold 27). In 1795, Connecticut sold the remaining territory (over 3 million acres) to the Connecticut Land Company for $1,200,000. The land company was comprised of “48 proprietors represent(ing) 204 individuals who had investments in the company” (27). While American Westward expansion is typically portrayed as a process where otherwise destitute settlers are offered opportunities in the form of cheap, “available” land, the Connecticut Land Company demonstrated how early American expansion was promulgated by a select few from the top down.

“But what if the colonizers are not dependent on native labour? — indeed, what if the natives themselves have been reduced to a small minority whose survival can hardly been seen to furnish the colonizing society with more than a remission from ideological embarrassment?”

Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology

Before purchasing the territories, speculators sent out “surveying parties” to the Western Reserve in search of potential dangers, profitable enterprises, and notable landmarks (28). One of these parties was headed by Moses Cleaveland (whom the city was named after in 1796). His party encountered a wide array of hardships. These included “clouds of mosquitoes, rainstorms, working in swamps, hot sun…, cramps from eating berries…, dysentery and intermittent fevers” (28). The Ellsworth family experienced this firsthand, with Daniel Ellsworth recording the death of two of his daughters to dysentery in his 8/22/1797 letter to John Wyles.

While environmental factors presented a considerable obstacle to settlers looking to colonize the region, the Western Reserve’s indigenous inhabitants offered even greater deterrence to the settler colonial endeavor. While partially motivated by exaggerated reports of native “barbarity”, the fact that “various militia organizations… were ordered mobilized at Cleveland for defense” highlights the threat posed by native groups and invites speculation as to claims of control (32). Moreover, the British continued to exert influence over many local indigenous groups, undoubtedly in an attempt to slow American imperial efforts. Nevertheless, native incursions demonstrated their continued resistance to colonialism and survivance in a now-contested borderland.Given the mileage of the journey, environmental resistance, and constant threat of native attacks, one shouldn’t be surprised to learn that the Connecticut Land Company suffered from poor sales. Despite this, New Englanders began to increasingly settle in the area. One reason for this was that the settlers had their “expectations shaped by the literature available to them before their journeys began” (Pallante 88). This literature painted a particularly rosy picture of frontier life, leaving settlers largely ignorant of the dangers ahead. Much of this literature can be understood as propaganda as it was produced by speculators to encourage Western settlement. In this context, the dynamics of settler colonialism in the Western Reserve involved complex relationships that a declension narrative fails to encompass, with various groups and individuals vying for survival in the borderland, often at each other’s expense.

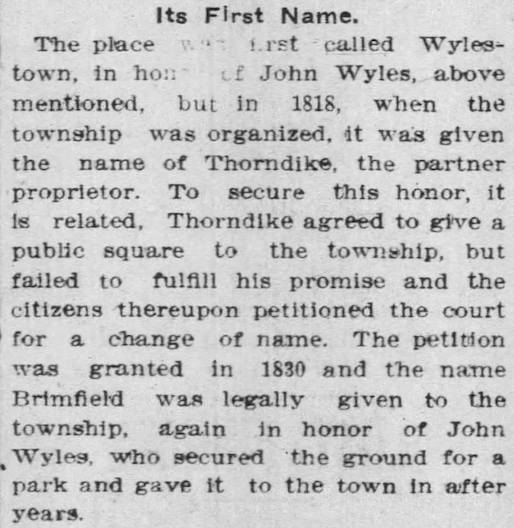

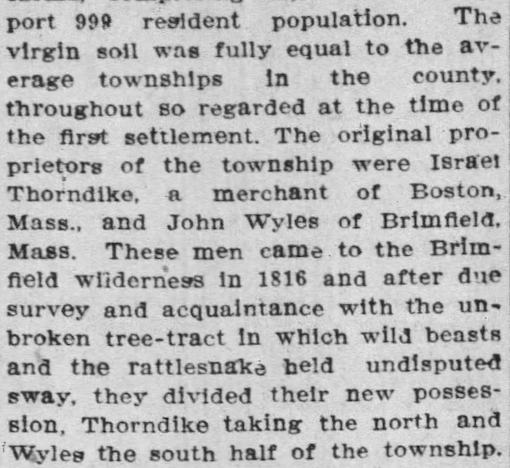

Brimfield, Ohio in Portage county, the namesake of Brimfield, Massachusetts, was one such settlement in the Western Reserve. In a speech, given by Dr. A. M. Sherman on July 4, 1881, Sherman explains how “in 1816 they [the settlers] came to this place, then an unbroken wilderness, inhabited only by wild beasts, and divided their interests.” The positioning of the territory that Brimfield, Ohio would come to inhabit as an “unbroken wilderness,” despite a documented history of indigenous persons, who had existed in the region centuries prior, suggests that the settler colonial project relied on the active denial of indigenous personhood and ownership over land that settler authorities had claimed. It is important to recognize that settlers, like “these people…of New England stock,” were not Native to, or had previously occupied the land which they were now claiming. The positionality of settler colonialists as inhabitants of previously occupied lands allowed towns, like Brimfield, Ohio, to strategically designate their accomplishments as “firsts of their kind,” despite the very real presence of a settled indigenous population in these regions that had likely performed similar tasks prior.

Anthropological discourses and theories absorbed many aspects of settler colonialism through what Wolfe describes as an “indirect set of connections between, on the one hand, a developing and substantially autonomous anthropological tradition and, on the other hand, the wider scientific and sociopolitical processes in which this tradition participated at both local and global levels” (Wolfe 5). Nationalism, an outgrowth of these anthropological processes upon which a settler colonial discourse is perpetuated, served a key purpose, even after the initial assembly of the community in 1816. Dr. A. M. Sherman’s July 4, 1881 speech pulls on State nationalism in service of magnifying how local dynamics, like settler colonialism, give rise to global phenomena. “How appropriate that you, quiet citizens of Brimfield, should assemble here to-day,” the speech begins, “to consider what you and your fathers and mothers have done in this quiet community, that has contributed to your country’s greatness and to your present peace and prosperity.”

Works Cited

“An Historic Old Town in Brimfield: An Interesting Article Concerning Its Early History.” Akron Beacon Journal, August 10, 1901, p. 81.

Lupold, Harry Forrest. “The Western Reserve as a Section in American History.” The Great Lakes Review, vol. 7, no. 1, 1981, pp. 24–36. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/20172565. Accessed 6 May 2024.

Pallante, Martha. “The Trek West: Early Travel Narratives and Perceptions of the Frontier.” Michigan Historical Review, vol. 21, no. 1, 1995, pp. 83–99. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/20173493. Accessed 6 May 2024.

Sherman, Dr. A. M. History of Brimfield: An Address by Dr. A. M. Sherman. Kent Bulletin Print, 1881.

Wolfe, Patrick. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology : The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. Cassell, 1999.